The regulations for medical devices are particularly important for AI systems in the healthcare sector. In addition, the forthcoming AI Act introduces key principles and will impose requirements on both manufacturers and users (e.g. healthcare organisations) of high-risk AI systems [32]. Although the AI Act has not yet entered into force in Norway as of 2024, it may be appropriate for organisations to begin considering its requirements now, particularly when planning to procure high-risk systems. The Personal Data Act and the general health legislation also provide important frameworks for the use of AI systems [33].

Intended purpose

The intended purpose of an AI system, i.e. the purpose for which the system is designed to be used, determines which regulations apply [34]. General-purpose AI models (GPAI models) [35] do not have a specific intended purpose on their own, but they can be incorporated into systems that has a medical purpose. They fall under specific regulations in the EU regulation for AI.

Under the Medical Device Regulations, AI systems are considered medical devices if they are intended for use on human beings for the purpose of diagnosing, preventing, monitoring, predicting, prognosing, treating or alleviating disease [36][37]. Other types of AI systems, such as those used for logistics or shift scheduling, do not typically fall under medical device regulations. However, AI systems like electronic health record systems may include additional functions that could result in their classification as medical devices. The EU Medical Device Coordination Group (MDCG) [38] has published guidance documents to assist in determining when software qualifies as a medical device under EU law [39].

- If the intended purpose is medical, the following applies:

- The AI system is considered a medical device, and the organisation must procure a CE-marked device [40]. The equipment must fulfil the documentation requirements set out in the Medical Devices Regulation.

- The AI system will generally be considered a high-risk system in accordance with the AI Act and must comply with the requirements set for these systems when the Act enters into force [41].

- If the intended purpose is not medical, the following applies:

- The AI system is considered a high-risk system under the AI Act if the intended purpose is listed in Annex III and must fulfil the requirements therein when it enters into force [42]. This applies, for example, if the AI system influences an individual's right to receive public benefits or health services [43]. In this case, public service providers are required to conduct a Fundamental Rights Impact Assessment (FRIA) [44].

- If the AI system is intended to interact directly with natural persons, the following applies, with some exceptions:

- The AI Act requires transparency: The AI system must be designed and developed so that affected individuals are informed that they are interacting with an AI system [45].

- Additionally, the organisation must assess whether the AI system may fall under other product legislation [46]. The section Alignment of product legislation on EU's website for the New legislative framework provides an overview of relevant product categoreis [47].

The legislation for medical devices [48]

The Norwegian laws and regulations on medical devices implement the EU Medical Devices Regulations (MDR and IVDR). If an AI system is to be used for a medical purpose, a medical device must be procured. While similar systems may be available on the market under other regulations, they do not meet the safety requirements for medical devices.

- Medical devices can only be marketed, distributed, or put into use when the devices comply with the fundamental requirements for safety and performance in accordance with the regulations, have undergone conformity assessment, and bear the CE mark, as outlined in § 7 of the Regulation on the use of medical devices (Håndteringsforskriften). This regulation require that the organisations ensure that medical devices are suitable for their intended use and that they are used in accordance with the manufacturer’s enclosed instructions for use.

Risk classes for medical devices

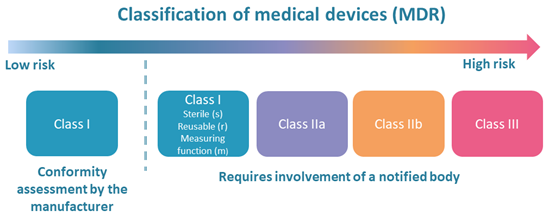

The extent of the conformity assessment required under the Medical Device Regulation depends, among other factors, on the risk class of the medical device [49].

Medical devices are classified into four risk classes (I, IIa, IIb and III) based on the level of risk associated with their intended use. For most types of class I devices, manufacturers may self-declare conformity. For class IIa, IIb and III devices (as well as equipment in classes Ir, Is and Im), a certificate from a notified body is required. An overview of classification rules can be found on the Norwegian Medical Products Agency website [50].

Medical devices intended for in vitro diagnostics (IVD) have their own classes (A, B, C and D) [51]. A certificate from a notified body is required for IVD equipment in classes B, C and D

Manufacturer responsibility

If a medical device is used for a purpose other than that stated in the declaration of conformity, or if the organisation modifies the device in a way that may affect compliance with the applicable requirements, the organisation assumes the legal obligations of a manufacturer under the MDR. This includes full responsibility for ensuring that the AI system meet all applicable safety and regulatory standards [52].

An example of this from diagnostic radiology [53]:

- An AI system developed for use in adults cannot automatically be used on children (ages 0–18). Children are not simply “small adults,” and special expertise is required to assess whether the AI system is safe for paediatric use and whether its performance on children is comparable to that on adults. If the system was CE-marked for adult radiology, but is intended to be used for children, it must be tested for the new age group through a clinical trial. In such cases, the organisation takes on manufacturer responsibility for the AI system.

Healthcare institutions may develop medical devices for internal use. The Norwegian Medical Products Agency's website provides guidance on the applicable requirements [54].

Transitional arrangements

Some medical devices currently on the market are still regulated under the previous EU regulations [55]. Transitional provisions have been introduced to bridge the gap between old and new regulations and to avoid shortages in the European market. For details, refer to the DMP’s website [56].

Clinical trial of an AI system that is not CE marked

If no suitable CE-marked alternative exists, or if an unmarked AI system is considered appropriate, organisations must apply for approval to conduct a clinical trial. Applications should be submitted to both the Norwegian Medical Products Acency(DMP) and the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics for Clinical Trials (REK KULMU) [57].

FDA approval

Medical devices that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [58], but have not undergone EU conformity assessed and do not carry the CE mark, cannot legally be used in Norway or elsewhere in the EU/EEA. They should therefore not be procured for clinical use. Manufacturers sometimes offer different models or versions of their devices for the U.S. and European markets. In such cases, it is important to ensure that the version being procured is the CE-marked model intended for use in the EU/EEA.

The AI Act

The purpose of the AI Act is to promote and increase the use of human-centred and trustworthy AI systems, while ensuring a high level of protection of health, safety and fundamental rights, including key democratic values, such as the rule of law and the environmental sustainability, against harmful effects that may result from AI systems. At the same time it aims to support innovation.

The AI regulation was published on 7th July 2024 [59], and its various provisions will enter into force gradually over time [60]. The Norwegian government has stated its intention to ensure that the AI Act is incorporated into the EEA Agreement as swiftly as possible [61].

To support compliance, the European Commission has mandated the development of harmonised European standards. These will provide technical specifications to help manufacturers and users meet the requirements set out in the regulation [62].

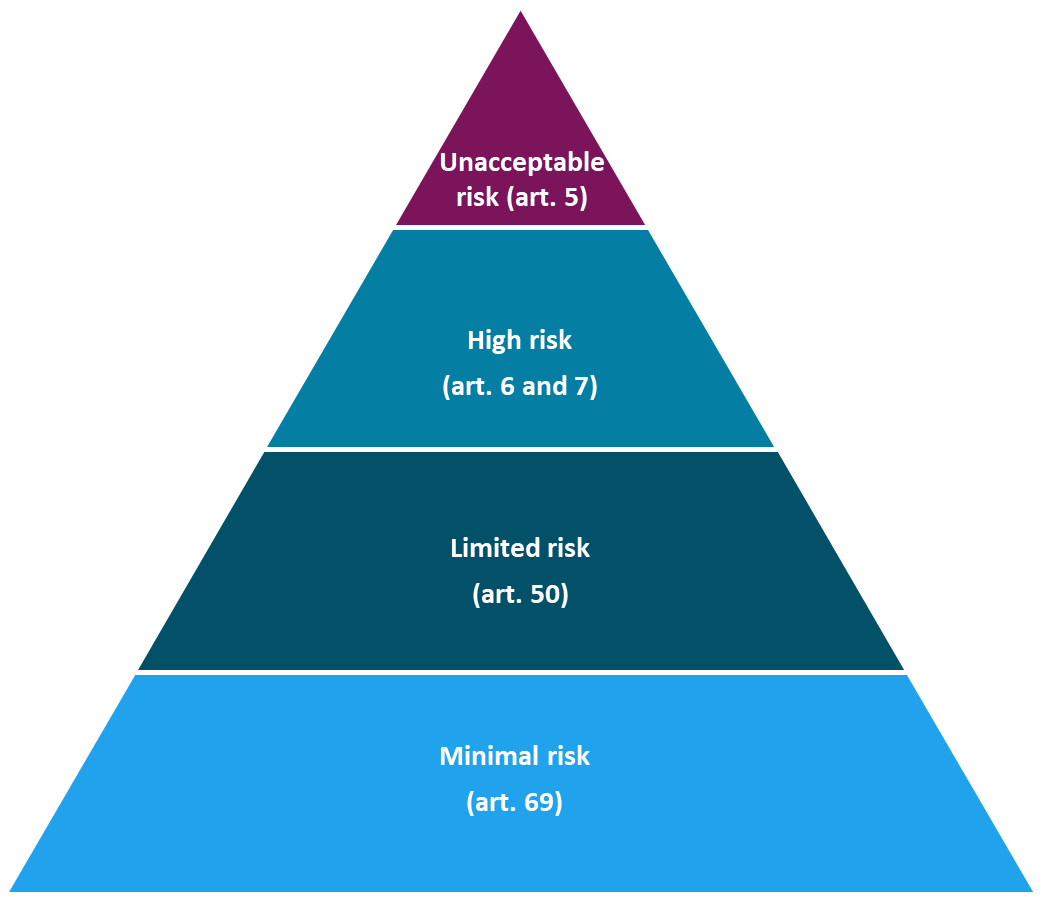

A key principle of the AI Act is that risk classification is based on the system’s intended use, not solely on the technical characteristics of the AI system itself. As a result, the same AI model may be considered limited risk in one application, but high risk in another, depending on the context in which it is deployed.

High-risk AI systems

The AI Act describes two categories of high-risk AI systems

Regulated products: Annex I of the AI Act

If there is a requirement for third-party certification of a product or safety component in a product that is already regulated by one of the EU regulations mentioned in Annex I, among others:

- Medical Device Regulation (MDR)

- In Vitro Diagnostic Device Regulation (IVDR)

- Machinery Directive, Toys Directive etc.

Regulated uses: Annex III of the AI Act

Stand-alone systems such as:

- Biometric identification, emotion recognition

- Critical infrastructure

- Education and vocational training

- Recruitment and working conditions

- Access to basic welfare services

- Law enforcement authorities

- Migration, asylum, border control

- Democratic processes and the work of the courts

The specific requirements for AI systems that are, or form part of, medical devices will apply from 2nd August 2027 [64]. For high-risk systems used for purposes listed in Annex III, the requirements will come into force on 2nd August 2026.

The AI Act outlines a number of mandatory requirements for high-risk AI systems, including:

- Risk management system (article 9)

- Data and data management (article 10)

- Technical documentation (article 11)

- Logging (article 12)

- Transparency and information to users of the system (article 13)

- Human oversight (article 14)

- Accuracy, robustness and cybersecurity (article 15)

Article 11 provides detailed requirements for the technical documentation that must be maintained for each high-risk AI system, and this is further elaborated in Annex IV of the AI Act [65]. While these provisions will not be legally binding in Norway until the regulation enters into force, this is documentation that suppliers will have to prepare as parts of the AI Act become applicable in the EU. They can already serve as a useful reference in the procurement process.

The concepts of transparency and human oversight (as described in Articles 13 and 14 of the AI Act) may be unfamiliar elements in the procurement process. A transparent AI system is designed in a way that makes it possible to understand how the AI model was developed. It should also be clear to users that they are interacting with an AI system. When users are aware that the system employs AI, they can take this into account when interpreting and applying the information it provides. Human oversight of an AI system may involve some form of human supervision or the ability to intervene when necessary. Users should not be entirely dependent on the system for making critical decisions. Ensuring effective human oversight requires, among other things, appropriate competence and training [66].

AI systems with limited risk

AI systems classified as limited-risk are not subject to the same stringent requirements as high-risk AI systems. However, they must still comply with certain obligations—most notably, that the systems are transparent, and that AI-generated content is labelled in a machine-readable format [67]. Organisations adopting such systems are also required to ensure that personnel responsible for operating or using the AI systems have adequate competence and training.

General Purpose AI Models (GPAI)

General Purpose Artificial Intelligence (GPAI) models [68] can be used either directly, such as ChatGPT and Gemini, or they can be customised and/or fine-tuned by other manufacturers for a specific purpose. Manufacturers relying on GPAI models must ensure they have sufficient documentation about the underlying model in order to demonstrate the quality and compliance of their own product.

Although the GPAI models do not have a specific intended purpose in and of themselves, they are still regulated under the AI Act if they meet certain criteria outlined in Article 51 [69]. Suppliers of GPAI models are, among other things, required to ensure that downstream users understand the models well enough to use them responsibly and lawfully in their own products and to meet their legal obligations [70]. If a GPAI model is considered to pose systemic risk, additional and stricter requirements apply [71]. Examples of systemic risk include the AI system's potential to influence elections, critical infrastructure and emergency preparedness. Suppliers of GPAI models with systemic risk must, among other things, conduct model evaluations to identify, and continuously assess and reduce systemic risks through risk management, post-deployment monitoring, and collaboration with relevant stakeholders. Serious incidents and possible corrective actions must be reported immediately to the European Commission and national competent authorities.

Pending the development of harmonised standards, the European Commission has launched a first draft of guidelines for GPAI models [72].

Other relevant regulations

AI liability directive

The European Commission has proposed an AI Liability Directive concerning non-contractual civil liability in cases where damage is caused by an AI system. The directive lays down common rules for the burden of proof in relation to high-risk AI systems, enabling claimants to better substantiate liability claims [73].

Automated decisions

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) contains several provisions related to automated individual decision-making, particularly Article 22, which concerns decisions made without human intervention. These provisions apply when AI systems make such automated decisions or are involved in fully automated data processing. Under the GDPR, individuals have the right not to be subject to a decision based solely on automated processing, including profiling, if the decision produces legal effects or similarly significant impact [74]. There are exceptions to this right, but in such cases, individuals are entitled to additional safeguards, such as the right to human review of the decision [75]. The GDPR also requires transparency and explainability regarding the logic underlying automated decisions, as outlined in Articles 13, 14, and 15 [76]. In Norway, provisions regarding automated decision-making are also included in Section 11 of the Patient Records Act (lovdata.no) and Section 21-11a of the National Insurance Act (lovdata.no), which permit the issuance of regulations allowing automated decisions in more invasive cases.

Rules on access to and use of health information

Under Norwegian law, health information is protected by a duty of confidentiality, and all processing of personal data must have a legal basis under Article 6 and Article 9 of the GDPR for the processing of health information [77].

A data controller is required for all processing of personal and health data [78]. The data controller is responsible for ensuring that the processing of personal and health data complies with applicable regulations. This includes ensuring that health data is processed lawfully, and that adequate information security and internal control measures are in place.

The GDPR provides the framework for the duties and responsibilities of the data controller and establishes the possibility of sanctions if these obligations are not met. Among the most important responsibilities are ensuring the lawful processing of health data, as well as maintaining satisfactory information security and internal governance.

The data controller may enter into an agreement with a data processor regarding the processing of personal data, a data processing agreement. This is relevant when another party is to process data on behalf of the controller. The data processor may only process the data in accordance with the agreement with the data controller.

See more about confidentiality and access to health information for validation in phase 5.

Radiation protection regulations

The introduction of AI systems may impact the use of radiation-emitting equipment or other areas related to radiation safety, such as decision support systems used to assess the justification for radiological examinations. Many of the relevant AI systems are used in radiology and radiotherapy. The radiation protection regulations impose strict requirements, including risk assessments, quality assurance and control of the systems and expertise among those operating them [79].

[34] Definition of "intended purpose" in the AI Act art. 3 no. 12 Article 3 Definitions (eur-lex.europa.eu) \and MDR art. 2 no. 12 (EUROPAPARLAMENTS- OG RÅDSFORORDNING (EU) 2017/745 (PDF))

[35] There is no official Norwegian translation. In this report, we rely on the Danish translation of the AI Regulation, which uses the term "AI-model til almen brug".

[37] See also the EEA supplement on medical devices here. EUROPAPARLAMENTS- OG RÅDSFORORDNING (EU) 2017/745 (PDF)

[39] Guidance on Qualification and Classification of Software in Regulation (EU) 2017/745 – MDR and Regulation (EU) 2017/746 – IVDR (health.ec.europa.eu)

[40] Handling regulations: Regulations on the handling of medical devices (lovdata.no)

[41] Systems are categorised as high-risk systems if: 1) it is included as a safety component in a product or the system itself is a product regulated by the regulations listed in Annex I and 2) must undergo third-party certification in accordance with the regulations in Annex I of the AI Act. Article 6.1 of the CI Regulation: Classification rules for high-risk AI systems (eur-lex.europa.eu)

[42] Article 6.2 of the AI Act: Classification rules for high-risk AI systems (europa.eu)

[43] Point 5 b and c in Annex III of the AI Act

[44] Article 27 of the AI Act

[45] Article 50 of the AI Act

[48] The Norwegian Medical Products Agency (DMP) is the technical and supervisory authority for medical devices in Norway and administers the product regulations for medical devices.[17] Further information can be found on DMP's website.

[52] See MDR and IVDR article 16

[53] AI models developed for use on adults cannot easily be used on children. See Use of Artificial Intelligence in Radiology: Impact on Paediatric Patients, a White Paper From the ACR Pediatric AI Workgroup (jacr.org)

[55] The Medical Devices Regulation (MDR) entered into force on 26 May 2021 and repealed Directive 93/42/EEC on other medical devices and Directive 90/385/EEC on active implantable medical devices with certain exceptions. The In Vitro Diagnostic Medical Devices Regulation (IVDR) entered into force on 26 May 2022 and repealed Directive 98/79/EC on in vitro diagnostic medical devices.

[56] Read more about transitional arrangements on the DMP website.

[60] Article 113 of the AI Act

[61] Digital Norway of the future - national digitalisation strategy 2024-2030 (regjeringen.no) p. 67

[63] The categories are described in Annexes I and III of the AI Act, respectively. The European Commission has the authority to amend the list of regulated uses in Annex III according to specified criteria, as set out in Article 7 of the AI Act.

[64] Article 113 of the AI Act and Annex III: High-Risk AI Systems Referred to in Article 6(2) (artificialintelligenceact.eu)

[66] Article 26 (2) of the AI Act on: Obligations of deployers of high-risk AI systems (eur-lex.europa.eu)

[67] Article 50(1)(2) of the AI Act: Transparency obligations for providers and deployers of certain AI systems (eur-lex.europa.eu)

[68] Article 3 (3) of the AI Act defines 'general-purpose AI model' as follows: means an AI model, including where such an AI model is trained with a large amount of data using self-supervision at scale, that displays significant generality and is capable of competently performing a wide range of distinct tasks regardless of the way the model is placed on the market and that can be integrated into a variety of downstream systems or applications, except AI models that are used for research, development or prototyping activities before they are placed on the market;

[69] Chapter V of the AI Act: GENERAL-PURPOSE AI MODELS (eur-lex.europa.eu)

[70] Article 53 of the AI Act: Obligations for providers of general-purpose AI models (eur-lex.europa.eu)

[71] Article 55 of the AI Act: Obligations of providers of general-purpose AI models with systemic risk (eur-lex.europa.eu)

[72] First Draft of the General-Purpose AI Code of Practice published, written by independent experts (europa.eu)

[76] General Data Protection Regulation: Avsnitt 2 Informasjon og innsyn i personopplysninger (lovdata.no)

[77] Read more about this on the Norwegian Directorate of Health's website on artificial intelligence: Regulations for the development of artificial intelligence – Norwegian Directorate of Health

[78] Controller is defined in the GDPR as a natural or legal person, public authority, agency or any other body which alone or jointly with others determines the purposes of the processing of personal data and the means by which it is to be carried out or as laid down in Union or national law, cf. Article 4(7). see also section 2(e) of the Patient Records Act, which refers to the definition in the GDPR with regard to who is responsible for the processing of health information in treatment-related health registers, including in patient records.