Executive Summary

Norway has high-quality health data, strong professional communities, a high level of digital maturity, and a society built on trust. Together, these provide excellent conditions for developing and implementing AI solutions in health and care services that are clinically relevant, professionally sound, and tailored to Norwegian needs.

Citizens are changing their habits rapidly. To offer useful health services, we need to meet people where they are and be willing to explore how new technology can change, improve, or create entirely new ways of delivering health services.

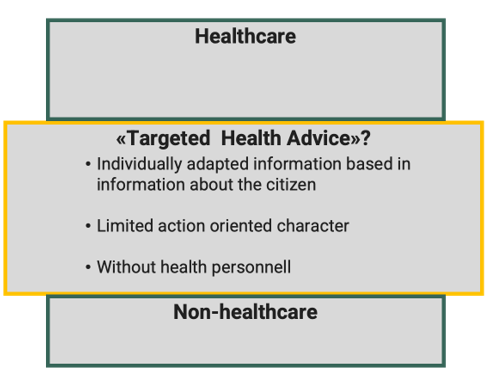

To establish a public AI service for health-related questions on Helsenorge raises there is a need to examine closely the concept of healthcare and the use of automated solutions. Today's distinction between healthcare and non-healthcare is challenged when AI provides tailored health advice without the involvement of professional healthcare personnel. We recommend investigating whether an intermediate level for targeted health advice is appropriate. Furthermore, the regulatory boundaries for automation should be reviewed, including which responses may be fully automated and when human oversight is required to ensure professional soundness, privacy, and patient safety.

Responsibilities must be clearly defined. We have assessed various models for roles and accountability. The Norwegian Directorate of Health could serve as a national entity with overarching responsibility for quality, compliance, and risk management of the public AI service. We also recommend ensuring that that knowledge bases and information sources are made AI-ready, and that a single responsible actor be designated with responsibility for knowledge and information management.

Technology choices should support a modular and model-agnostic architecture. A quality framework should be developed to promote predictability, auditability, and transparency. The AI service must also incorporate guardrails and systems for continuous quality and deviation monitoring. Establishing and operating a public AI service involves high complexity and risk, and will require clear frameworks, requirements, and incentives to enable a well-functioning ecosystem.

We propose a phased introduction of sub-services, in collaboration with relevant professional communities. The first phase should prioritize low. Risk, high-benefit areas such as plain language explanation of lab results and discharge summaries, national scaling of existing triage pilots, selected prevention and follow-up services, and/or targeted services for specific patient groups. This can likely be done within existing legal frameworks.

To progress further, fundamental questions must be examined and resolved. The Norwegian Directorate of Health will initiate activities that are critical for continued advancement. This includes defining what an AI service that provides targeted health advice actually entails, assessing potential benefits and consequences for the health service, and entering into binding collaborations with relevant stakeholders.

Objectives of a Public AI Service Providing Health-Related Advice

The Ministry of health and care services has requested that the Norwegian Directorate of Health makes a preliminary assessment regarding the establishment of a public AI service that can responds to health-related questions from citizens. The service is intended to strengthen the publics' ability to manage their own health. According to the mandate, the long-term objective isto establish a service that can provide individual healthcare. The service can be developed in phases, where the first phase may be a service that is not defined as healthcare. The Norwegian Directorate of Health has been given a short time to deliver on a complex order, andwe consider further work on such a service both important and necessary.

Rapid and widespread use of international AI assistants among the general public is largely due to advantages such as high accessibility, good user interfaces, anonymity, and an expectation of quick and useful answers. Studies have shown that 78.4% of users are willing to use ChatGPT for self-diagnosis.[1] Individuals have little opportunity to assess the quality of such AI services, and there is limited insight into the underlying data and quality assessments. The quality of advice given by consumer AI assistants are not subject to regulatory oversight. This introduces risks related to misinformation, unwarranted confidence in the guidance provided, and increased demand on the health service in cases where neither sources nor outputs are subject to adequate quality assurance.

The goal of a public AI service is to increase health literacy in the population and enable the public toto take better care of their own health. The Norwegian Directorate of Health will explore how AI can change and create new ways of delivering health services, in ways that supplement, rather than compete with, the large international AI actors. The public AI service will supplement digital services on Helsenorge, where the public also will have access to general health information, their own health data, and self-help tools. The service will be established within an ecosystem in which several actors may contribute sub-services, such as plain language modules, quality-assured knowledge sources, and language models specialized for health. Collectively, this can make the service relevant and attractive to residents, guide them to the right level of healthcare, reduce the burden on healthcare personnel, support business development, and thus contribute to a sustainable health service. The service can be introduced in phases: first as a platform that consolidates health information from various actors, next as a solution that offers targeted health advice, and, over time, as a service that may provide elements of "automated healthcare".

Legal Framework

Artificial intelligence introduces new opportunities for how we can respond to the needs of residents. To explore the potential scope of a public AI service, it is necessary to understand the current legal framework. This framework is grounded in existing legislation, including the Health Personnel Act, the Patient and User Rights Act, the Health and Care Services Act, the Specialist Health Services Act with accompanying regulations, and radiation protection regulations. Furthermore, human rights, the Constitution, as well as other regulations such as the Equality and Anti-Discrimination Act and the Public Administration Act apply. EU legislation incorporated in Norwegian law through the Medical Devices Regulation and the Personal Data Act, while the AI Act has just been subject to public consultation.[2]

For all AI tools that process personal and health data, the general requirement is that such processing must comply with confidentiality obligations and the principles set out in the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The data controller is responsible for ensuring that the use of an AI tool occurs within these legal boundaries.

As with the introduction of any new technology in the health sector, the development and use of AI may involve new types of risk. It is important to emphasise that the requirements set out in health legislation for organisations and health personnel providing healthcare also apply here. This includes, for example, the requirement of professional soundness under Section 4 of the Health Personnel Act, confidentiality under Section 21, and documentation obligations under Sections 39 and 40. Under the Patient and User Rights Act, patients have, among other things, rights to information, participation, and access to their medical records. However, the definition of “healthcare” is broad, and it is not always clear where the line should be drawn between general health information and healthcare. The Norwegian Directorate of Health has identified several factors that are relevant to this assessment.[3]

The EU Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act) builds on and supplements adjacent legislation such as the GDPR, the Medical Devices Regulation, and national health legislation. The regulation adopts a risk-based approach, in which each AI system is classified according to a level of risk that determines the requirements a provider or deployer must meet. Risk classification is based on the intended use of the AI system, and the categories are minimal, limited, high, and unacceptable risk. The regulation also contains specific requirements for providers of General-Purpose AI (GPAI) models, which can be an integrated part of an AI system.[4]

AI tools used for general health information will, in the Directorate's assessment, be considered an AI system with limited risk. Furthermore, AI tools used for healthcare will, generally, constitute high-risk AI systems. The requirements applicable to these types of AI systems, as well as to general-purpose AI models, are described in more detail on the cross-agency information page on AI.

Targeted Health Advice to the public

The development of AI services in healthcare raises fundamental questions concerning how we understand healthcare, where the boundaries lie between technology and human control, and how such services may influence long-standing Norwegian welfare and societal traditions:

- How can an AI-based health service ensure trust and quality, as well as equitable access, without weakening the overall health service?

- Where is the boundary between general health information and individual healthcare?

- What can and should be automated in a public AI service?

Trust and Quality

Many people are open to using AI services for health advice[5], yet no quality-assured public alternatives are currently available. The public healthcare system in Norway enjoys a high level of trust. Both trust and patient safety may be undermined if AI services are offered without clear accountability and quality assurance, as this increases the risk of misinformation.[6],[7]

A chat-based service may convey a sense of empathy and understanding, but it may also create problematic psychological dependence among users[8] and challenge the traditional relationship of trust between healthcare personnel and patients. It remains unclear how such a service would affect the utilisation of traditional healthcare services. Could it increase pressure on an already strained sector, alter communication patterns with healthcare personnel[9],[10],[11], or lead to more people seeking a second opinion? AI solutions may also lead to shifts in tasks and collaboration patterns across professional groups, and will require that competence, training, and support structures develop in step with the technology.

Strengthening the population’s health literacy. The aim of a public AI service is to enhance health literacy in the population and enable individuals to take better care of their own health. A further goal is to strengthen people’s general understanding of AI, particularly generative AI, so that they are better equipped to critically assess information provided by a chat-based service. At the same time, those who do not wish to use, or are unable to use, digital health services must have access to equivalent alternatives. It is important to recognise that such a service may widen the digital divide in the population and, in this context, contribute to increasing health disparities between those who use digital services and those who do not.[12]

Healthcare, Targeted Health Advice, and Health Information

Healthcare is defined as “any action that has a preventive, diagnostic, therapeutic, health-preserving, rehabilitative, or caregiving purpose, and which is performed by healthcare personnel.”[13] Once healthcare is provided, the services must be professionally sound, and the obligations set out in the Health Personnel Act, such as those related to information and documentation, must be fulfilled by the healthcare personnel involved.[14]

When the legislation was drafted, it was hardly conceivable that machines, such as AI systems, could produce advice that resembles, and may be perceived as, healthcare. An AI service that generates content without involving healthcare personnel will, in principle, fall outside the statutory definition of healthcare. Even if such an AI service is not covered by the definition, it may nevertheless be perceived in practice as having a preventive, diagnostic, or therapeutic function for the individual. A generative AI service may give users the impression that they are receiving professional healthcare because its language, structure, tailoring, and references to medical knowledge can imitate how healthcare personnel provide advice. As a result, users may readily attribute the same weight and authority to such advice, even though the system lacks both legal responsibility and the human clinical judgement required in the health service.

If the AI service is offered through a public platform such as Helsenorge, users may assume that the information is as safe and quality-assured as formal healthcare. However, this may create a false sense of security if the quality varies. It is therefore essential to appropriately frame a public AI service so that clinical and legal responsibility is upheld.

The concept of healthcare, as defined in the Health Personnel Act, is binary: an activity either constitutes healthcare or it does not. This binary distinction may be insufficient with the introduction of AI. There is thus a need to consider the possibility of establishing an intermediate category between healthcare and non-healthcare

A public service that provides targeted health advice may involve situations where individuals have the option to share their own information, and the response is only partially actionable in nature. If a public AI service offers something beyond general health information, yet does not constitute healthcare, it must be clearly defined which rights and obligations apply. This may necessitate an assessment of whether new regulation is required.

Automated Service

One of the aims of a public AI service is to enable individuals to manage their own health to a greater extent. An AI service that processes health data in order to provide tailored, automated health advice to individuals will, as a general rule, be prohibited under Article 22 of the GDPR if the advice produces legal effects for, or significantly affects, the individual. For an AI service to provide such advice without violating this prohibition, there must either be an active and informed consent from the individual or another legal basis for providing such advice. In addition, appropriate measures must be in place to ensure, among other things, human involvement and accountability, as well as transparency.

It may be possible to design an automated AI service that provides targeted health advice which does not produce legal effects for, or significantly affect, the individual, but which is nonetheless useful. It may therefore be desirable to make use of opportunities for automation for this type of AI service.

Figure 2 describes three levels of automated AI services and provides an example of how one type of AI service (for tick bites) could appear at each level. The levels are intended to be general and may, for example, be applied both in preventive contexts and in follow-up after completed treatment.

| Leve | Requirements | Example: tick-bite |

|---|---|---|

Automated healthcare

|

|

|

Targeted health advice

|

|

|

General health information

|

|

|

Organization and Responsibility Models

The development of a public AI service requires clear responsibilities and robust organisation to ensure quality, trust, and long-term sustainability. Clear roles, anchoring within the health sector, and coordination across professional environments and administrative levels are essential. If a public AI service is to be established, the following fundamental questions regarding responsibility and organisation must be addressed:

- How should the responsibility model for a national AI service be structured, given the current division of responsibilities between the primary and specialist healthcare services?

- How can health knowledge sources be managed coherently to ensure the quality of the public AI service?

There may be a need for two new roles: a national responsibility for a public AI service with entry on Helsenorge and a national responsibility for knowledge and information management, see Figure 3.

National Responsibility for a Public AI Service

The Government has appointed a Health Reform Commission tasked with assessing and proposing new models for the future organisation, management, and financing of the health and care services in Norway. Several pilots for new ways of organising health services, referred to as “Project X”[15], are currently under way, and it is natural that any future organisation of a public AI service should take this work into account.

The Norwegian Directorate of Health considers it appropriate that a single organisation holds the overall responsibility for a public AI service that provides targeted health advice. This responsibility includes ensuring compliance with relevant legislation and safeguarding ethical considerations, professional soundness, and quality at all stages. The principles set out in the Regulation on Management and Quality Improvement in the Health and Care Services and the Patient Injury Act should also apply to this organization.

Such comprehensive responsibility entails establishing clear requirements and frameworks for all actors contributing to the ecosystem, whether through quality, collaboration, data, AI models, solutions, or sub-services. Risks stemming from the international and political landscape can be managed through model-agnostic orchestration, which enables switching suppliers in the event of political or regulatory changes.

The Ministry of Health and Care Services (HOD) may designate an existing organisation and assign it expanded responsibility or establish a new organisation. The Norwegian Directorate of Health considers the following options most relevant for assuming such expanded responsibility:

The Norwegian Directorate of Health could establish a new department or a (new) subordinate agency. The advantages are that the Directorate is the national authority for digitalisation and information management in the health and care services, which includes responsibility for providing reliable, up-to-date, and research-based health information to the public. The Directorate also holds responsibility for national clinical guidance and standardisation, publisher responsibility for Helsenorge, meaning ethical and legal responsibility for its content, and a national mandate spanning both primary and specialist healthcare. However, the Directorate does not hold a formal responsibility for delivering healthcare, nor does it provide healthcare services itself. This must be considered in light of the recommendation to assess a new type of service offering targeted health advice. The Directorate is positive towards assuming expanded responsibility but considers that this should be examined further.

The specialist health service could be assigned this responsibility, either by assigning it to one Regional Health Authority (RHF) or by allocating joint responsibility to all the RHFs. The RHFs already have a statutory obligation to provide healthcare services. They are tasked with assisting the health communities with management data. However, they have no responsibility related to the first line or across the specialist and primary health services, and they have few, if any, patient-facing services across regions. They also do not have a regulatory authority role.

National Responsibility for Knowledge and Information Management

AI-ready knowledge sources that are updated, accurate, and aligned with medical and health science knowledge, form the foundation for the development of AI models and services.

The knowledge landscape in the Norwegian health sector is characterised by uneven quality, declining access to key sources, dispersed and fragmented dissemination, and increasing dependence on commercial actors.[16] Figure 4 shows the number of articles per content-owner on Helsenorge. The content has been developed gradually over many years, with various actors, resulting in uneven coverage. Some areas are extensively described, while others are more fragmented.[17]

A wide range of actors produce, manage, and disseminate health information, from national authorities and institutions to professional communities, the specialist health service, and municipal services. The responsibility for keeping information up to date and quality assurance is distributed across many actors, and there is no overarching structure that ensures coherence and consistency in communication to the public.[18]

The introduction of AI services may amplify these challenges. AI systems rely on available sources, but when those sources are incomplete, inconsistent, or overlapping, the risk of misinformation, conflicting advice, or individuals receiving different information depending on the entry point increases. This can undermine both quality and public trust. Denmark, for example, has coordinated activities related to providing health information to the public.

A national approach to knowledge and information management and governance should aim to collect, structure, and quality-assure health information across actors, and set requirements for how data may be used in AI services. It would be beneficial to consider the sources used for services directed at both the public and healthcare professionals in a unified manner.

A single actor should be given responsibility for gathering and managing health-related knowledge and information, ensuring that sufficient, high-quality sources are available to provide the population with relevant and tailored health advice and health information. This includes, among other things, responsibility for ensuring the quality of data sources and coverage of all relevant professional fields and service areas, based on Norwegian health expertise, practice, values, legislation, and ethics.

Below are some alternatives the Norwegian Directorate of Health considers most relevant for assuming such expanded responsibility.

The Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH), including the Norwegian Electronic Health Library and the National Poisons Information Centre, already holds a broad national responsibility as a knowledge producer for public authorities and the health services, and has extensive experience in information management as the custodian of health registries. NIPH also contributes patient-directed information (via Helsenorge.no) and gathers knowledge from registries and surveys. The normative authority is, however, limited to infection control.

The Norwegian Directorate of Health already holds the responsibility as publisher for the informational content on Helsenorge, coordinating responsibility for the information content in the ETI solution (Easier Access to Information, cross-sectorial information to parents with children with complex needs), and a regulatory role to safeguard the interests of the public, spanning both primary and specialist healthcare. The Directorate is also responsible for national medical and health-professional standardisation. Through these tasks, as well as through the publication of analyses, statistics, data, and indicators, the Directorate has substantial experience in information management. Furthermore, the Norwegian Directorate of Health provides a significant amount of patient-directed information, including via Helsenorge.no and through public information campaigns. HELFO is responsible for the chatbot currently available on Helsenorge.

The specialist health service is a major producer of knowledge related to diagnostics, treatment, and follow-up, and has several relevant cross-regional responsibilities. Examples include FNSP (information on services and treatment options), Metodebok.no (diagnostics, treatment, prognosis, and follow-up), and SKDE (improving knowledge about treatment quality and use of specialist healthcare services). However, the scope only to a limited extent encompasses the primary healthcare services and the perspective of the general public.

Technology and Data

A public AI service must offer something that international actors cannot, namely trust, transparency, quality, and secure data processing. This raises several fundamental questions related to data and model development:

- What should Norway retain control over in order to ensure national digital autonomy?

- How can we ensure that AI services preserve language and culture in Norway?

- How do we best approach the development of a public AI service, given available technologies and resources?

- How should the actors in the ecosystem be involved and engaged?

International and Political AI Landscape

Technological development is influenced by the international and political landscape. Divergent regulatory approaches internationally, for example between the United States and the EU, may create areas of tension, particularly if a public AI service becomes too closely tied to U.S. platforms.

For instance, in July 2025 the U.S. President issued an order requiring federal agencies to procure AI models that promote truth-seeking and “ideological neutrality,” while at the same time problematising the use of concepts such as DEI (Diversity, Equity & Inclusion), critical race theory, transgenderism, unconscious bias, intersectionality, and systemic racism in contracts.[19] Although this applies to federal procurement, it may indirectly influence commercial offerings. For Norway, this entails a risk that U.S.-developed AI models may reflect U.S. political directives, including in health-related responses.

The development and use of European, Nordic, and Norwegian AI models, as well as the establishment and utilisation of data centers and infrastructure, should therefore be viewed both as a technological investment to support public AI services and as an investment in digital autonomy and political risk management.

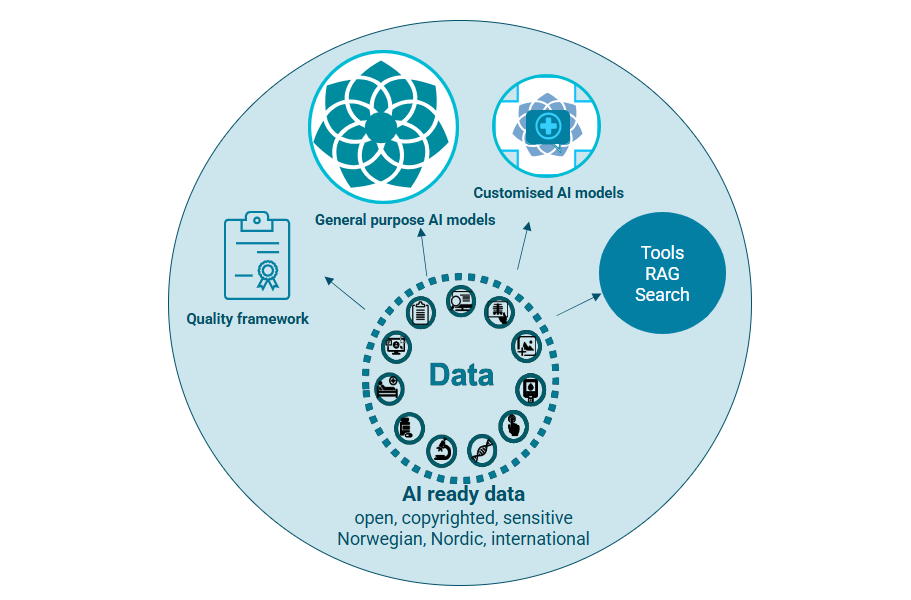

Quality-Assured Data

Building a high-quality AI service requires a quality-assured foundation of data with updated and relevant knowledge and information sources. Such data may be open and freely available (from the internet), protected by copyright (textbooks), or protected by confidentiality (medical records). The information must be processed in various ways to become AI-ready.

AI-ready knowledge and information sources can be used both to improve AI assistants from the large global actors, to train new models, and to improve and validate our own AI services.

Data sources can be prepared to make them visible in AI models on open platforms through, for example, Generative Engine Optimization (GEO), which is particularly relevant given the increasing use of 'zero-click searches.'[20]

Data sources can be used for training and fine-tuning Norwegian health AI models, in collaboration with the National Library and other relevant actors. An important aspect is ensuring that the languages used in Norway (such as Bokmål, Nynorsk, and the Sámi languages) are supported within the service.

The data sources may also be used to guide AI systems to rely on selected knowledge sources when generating responses, thereby enabling the production of more precise and factual answers[21], for example through Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) solutions. RAG solutions based on Norwegian/Nordic sources may help ensure that responses are grounded in local standards rather than foreign ideological perspectives.

In addition, the data sources are essential for testing and evaluating both individual components and the AI service as a whole within the proposed quality framework.

Building models

AI models are the most important component of an AI service. AI models vary significantly in nature, and these distinctions are essential. They can be predictive (image analysis) or generative (language models). A generative model can invent answers ("hallucinate"), produce different responses to the same question, and it is considerably more difficult to verify and quality-assure than a predictive model. An AI service may rely on a single AI model or a combination of several models.

The most well-known AI models are large and designed for general-purpose use, whereas AI models may also be small and dedicated to specific diagnoses, subject areas, or work processes. For example, the National Library plans to offer general models for free use by the Norwegian public, which can then be further trained for more specialised applications, such as in health. The first experimental models are planned for early 2026. Nordic languages are closely related, making Nordic cooperation a relevant possibility.

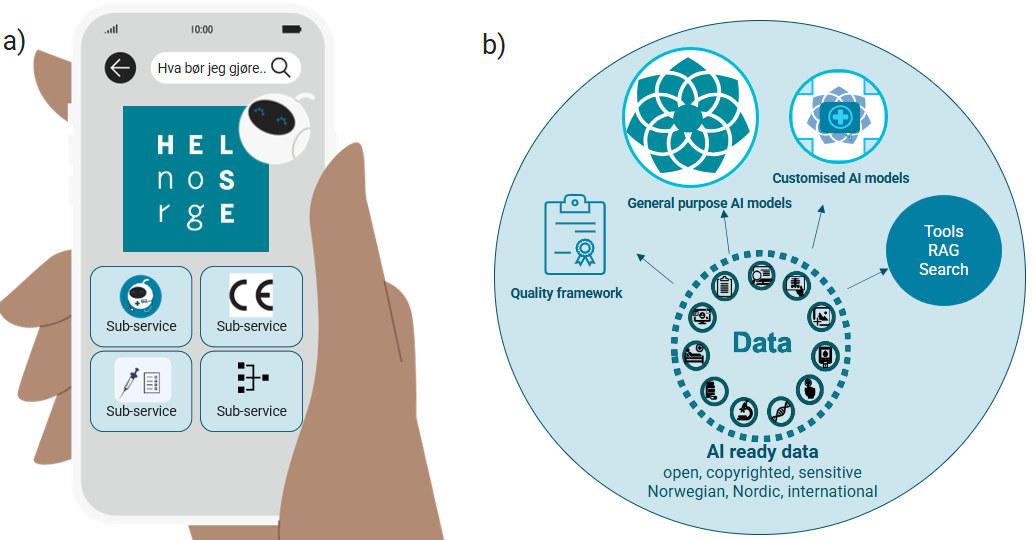

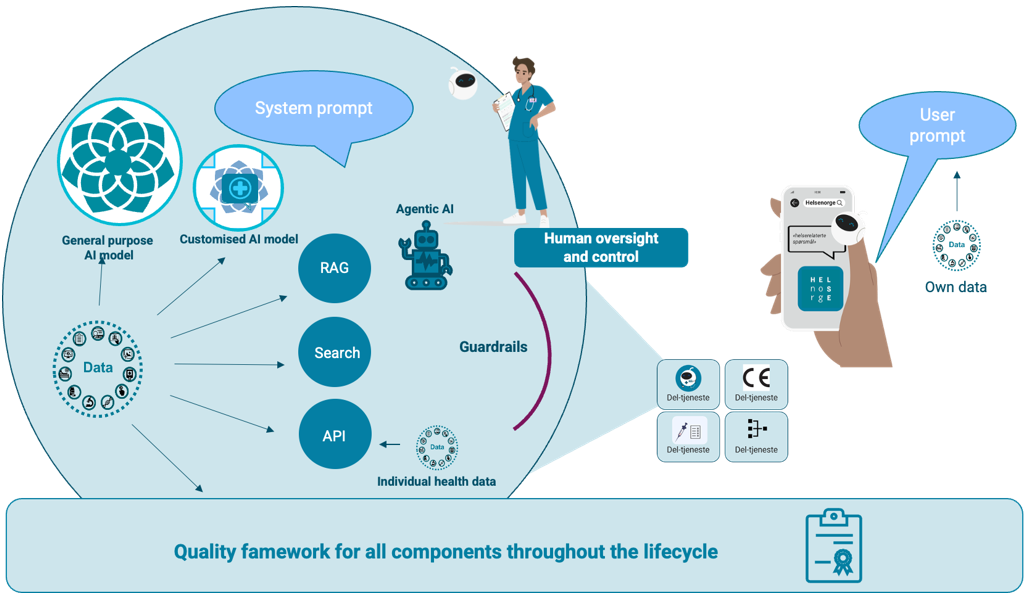

A future-oriented AI service should combine existing solutions, further developed components, and new models. As AI technology evolves rapidly, it is essential to facilitate regular updating of data and replacement of technological components, as illustrated in Figure 6.

In this context, a tool refers to a module or component that performs a specific task. Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) and search are two types of such tools. Another type of tool may provide access to individual health data and health registries through API solutions, which can be used to tailor responses to the individual. Agentic AI refers to the process that orchestrates the use of different tools.

Guardrails can be used to filter, for example, errors or biases. A system prompt is an instruction used to guide an AI system in how it should respond to user input, for example by ensuring that responses are based only on specific sources.

A user prompt[22] is provided by the user in a text-based dialogue (chat dialogue) with the AI service and may include the user information, lab results, or images. The dialogue is used to understand what the user is actually asking about and thereby to generate more precise responses from the AI system.

Human testing, oversight, and regular monitoring of the system are essential to ensure accurate, ethical, and responsible decisions, elements that the technology alone cannot guarantee. (This does not necessarily mean that humans must be involved in producing the responses given by the AI service.)

The public AI service must be subject to systematic and comprehensive evaluation to ensure professional soundness. A quality framework is needed, with principles and standards for quality, including tools to measure and reduce the risk of hallucinations, and to support greater predictability, auditability, and transparency.[23] Evaluations must include language (Bokmål, Nynorsk, Sámi), cultural adaptation, and medical and health-science knowledge and practice. Practices to ensure that performance and robustness remain within the quality requirements over time should be ensured, even during rapid changes in models.

The service should be built in a modular manner, using components that collectively ensure both quality and a good user experience. As AI technology evolves rapidly, the solution must therefore facilitate updating of data and replacement of technological components.

Ecosystem for a Public AI Service

Establishing and operating a public AI health service involves high complexity and risk and will require significant effort from many actors with different responsibilities.

The public AI service can become available on Helsenorge and consist of several different sub-services. Multiple actors may be relevant as providers of sub-services and components for the AI service, as illustrated in Figure 7 below. Examples include developers of AI models, providers of knowledge, information and datasets, producers of CE-marked solutions, infrastructure suppliers, and the health industry and R&D institutions in general.

Orchestrating such an ecosystem will be complex and may involve managing agreements with multiple actors, including data providers, developers, and suppliers. AI services must be able to rely on up-to-date technology at all times. The choices made must support a modular and flexible interaction between different technologies, keeping pace with rapid technological development. This requires a high level of AI competence.

Most of the relevant sub-services will be costly to develop, particularly if they are to be CE-marked. Achieving CE marking requires clinical studies and extensive documentation, which is both time-consuming and resource-intensive. This must be taken into account in the incentives offered.

Further work

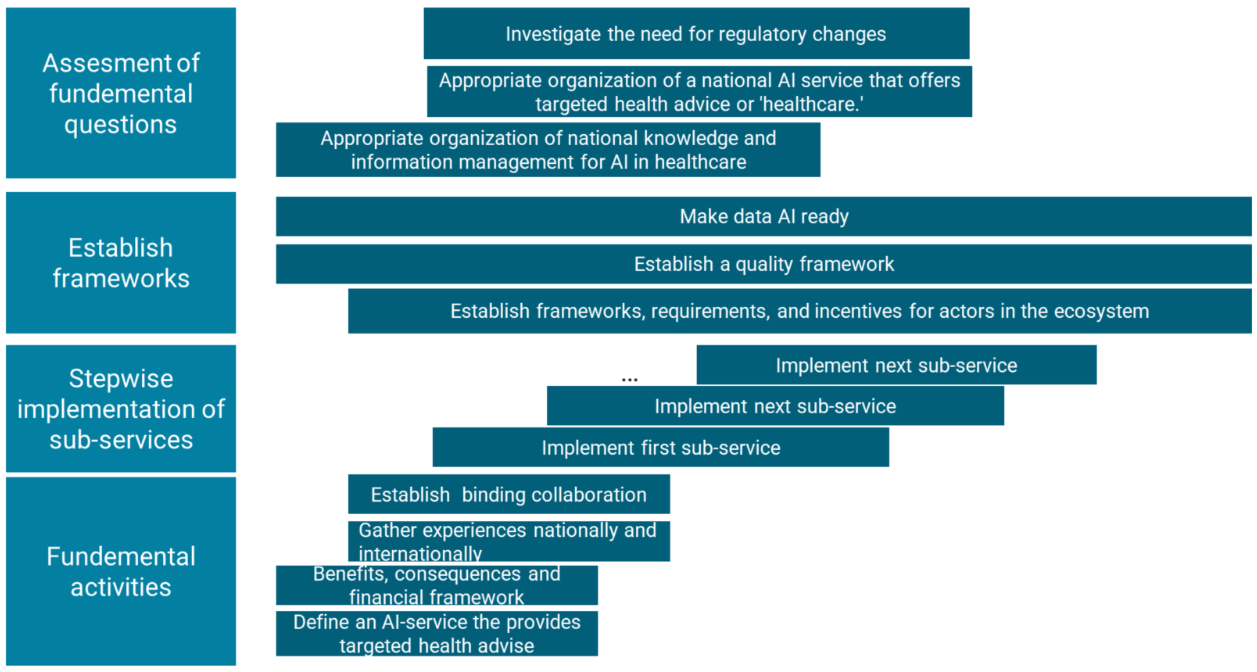

Stepwise Development

The first step should be to establish sub-services that provide high benefit with low risk within a relatively short timeframe, for example:

- advancing the work of NHN, which is responding to the mandate to use AI to simplify access to general information and tools available on Helsenorge.

- expanding the Directorate of Health’s dietary guidelines to include targeted nutritional advice.

- establishing a new service that translates medical information into plain language and helps individuals understand medical information they have received, either from an open AI service (such as ChatGPT) or from the health service itself, such as test results, treatment pathways, or medication overviews.

- advancing one or more existing triage pilots to a national solution, for example the triage solutions being tested in Kristiansand municipality or at the Student Welfare Organisation in Oslo.

- advancing a pilot on vaccine advice for the public (NIPH), potentially including the childhood vaccination programme.

- establishing or scaling other services for prevention, patient follow-up, or specific patient groups to a national service, for example within mental health.

The first step involves assessing these candidates and determining what is required for them to become national services. This includes evaluating who should hold responsibility, whether legal amendments are necessary, the technological frameworks needed to support a stepwise development process, and the need for financing.

At the same time, potential benefits and consequences of the service should be assessed, including its impact on the use of traditional healthcare services and whether the AI service enhances opportunities for self-management.

It will also be important to systematically gather national and international experience from similar and related initiatives, including mapping comparable services in other countries and examining how others approach knowledge and information management, quality work, and the operation of ecosystems surrounding AI development.

In parallel with developing a first version of the service, it will be appropriate to invest resources in making data AI-ready, establishing a quality framework, and developing clear frameworks, requirements, and incentives for the actors contributing to the service. This will provide a solid foundation for both new and improved services with strong control over sources and content.

Fundamental questions related to responsibility, legal frameworks, needs, and consequences must be clarified before a public AI service can be established. The Norwegian Directorate of Health will initiate work on these clarifications immediately.

Involvement of Actors in Further Work

The Norwegian Directorate of Health will establish collaboration within health administration, with among others the Norwegian Directorate of Health, NIPH, DSA, DMP, the Norwegian Board of Health Supervision, and NHN, which will respond to the recommendations in this response. The collaboration can build on experiences made through the work in the AI advisory board for health and care services.

To align the work with the needs of the population we will involve among others, user and family organizations, patient organizations, the user board in the Norwegian Directorate of Health, and DigiUng's youth panel. The Norwegian Medical Association will also be involved.

To ensure professional anchoring, relevant digital service providers, developers of AI models, owners of knowledge and information sources, infrastructure providers, industry actors, health clusters, and research and innovation environments will be engaged.

The National Library may contribute to the development of AI models tailored to Norwegian conditions. It has received a national mandate to establish an “AI Factory,” including financing and management of content rights for model training, infrastructure, and staffing.

The Norwegian Digitalisation Agency has national responsibility for establishing KI-Norge and national shared solutions for service infrastructure, including those that support the development of RAG solutions.

Nordic and European collaboration arenas include the Nordic Council’s initiative New Nordics AI, intended as a toolbox and platform for knowledge exchange among the Nordic countries.[24]

HELFO has developed a chat solution on Helsenorge and maintains a competence environment related to its operation. This solution can be expanded with more health-related content. This approach enables a safe and secure pathway to progress to the next development stage while gathering valuable insight along the way. Such a project can be realised quickly, as the organisational structure is already in place.

The Norwegian Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority (DSA) provides advice on health preparedness in the event of nuclear accidents (iodine tablets) and nuclear incidents; guidance on UV exposure; advice on living conditions following nuclear medical treatment; measures related to radon exposure to reduce lung cancer risk; risks associated with medical radiation use; and advice related to exposure to electromagnetic fields (mobile phones and wireless networks).

NHN has received an assignment in the 2025 enterprise meeting to adopt AI to simplify access to general information and tools available on Helsenorge. NHN’s mandate is limited to health information.

Some identified relevant and related initiatives include: Helsesvar (DigiUng); Easier Access to Information (ETI) (Life Event: children with complex needs); Studenterspør.no (all student welfare organisations); Nettlegen (Kristiansand municipality); Cross-Language Effective Communication (Police Directorate); Helsehjelp Pilot (Kristiansand municipality); the triage pilot (Student Welfare Organisation in Oslo); and the Tick Centre (Ministry of Health and Care Services, South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority, and Sørlandet Hospital).

Experiences from Other Countries

There appear to be few countries that offer a national digital health service based on AI.

- NHS England plans to launch My Companion, intended to give patients access to reliable health information, help them articulate their health needs and preferences, and provide information about their health condition or upcoming treatment.

- WHO (World Health Organization) has developed the prototype SARAH (Smart AI Resource Assistant for Health), a generative AI-based chatbot with an avatar that can speak or chat with users. It is designed to provide reliable health information globally on health-promoting behaviours (smoking cessation, physical activity, diet, stress management, mental health) and is available in eight languages. WHO has been explicit that SARAH does not provide medical advice.

- NHS 111 Wales offers an AI assistant, available in multiple languages, which retrieves information from the NHS 111 website based on patient prompts. The solution has been developed in collaboration with private actors that supply AI technologies.

- Omaolo (Finland) is a national health and care service. It supports self-management and helps individuals contact the public healthcare service when necessary. Omaolo consists of several modules, some of which are CE-marked as medical devices.

- 1177 “Direkt” (Sweden) is being rolled out as a first-line chat service. The service has been subject to regulatory review and public debate following deviations in triage outcomes (estimated “3 out of 10” in the early phase). Key lessons include the need for quality assurance, monitoring, and clearly defined responsibilities from day one.

Summary of Recommendations and Overall Plan

Main Recommendations

The main recommendations are:

Fundamental Activities

- The Norwegian Directorate of Health will initiate work to establish a public AI service that responds to health-related questions. The work must define what an AI service that provides targeted health advice entails.

- The Norwegian Directorate of Health will make an assessment of benefits (costs and benefits) and consequences for the health service and healthcare personnel.

- The Norwegian Directorate of Health initiate a collaboration within health administration, with among others the Norwegian Directorate of Health, NIPH, DSA, DMP, the Norwegian Board of Health Supervision, and NHN, which will respond to the recommendations in this response. Relevant environments are invited to binding collaboration in various measures where relevant. In the further work, the Norwegian Directorate of Health will contact relevant institutions and organisations, both nationally and internationally, that offer or are planning similar services, and will gather the experiences and assessments they have made

Stepwise Establishment of Sub-Services

- The Norwegian Directorate of Health will start work to establish the first sub-service(s).

Establish Frameworks

- The Norwegian Directorate of Health will initiate work to establish clear frameworks, requirements, and incentives for delivering services and solutions in the ecosystem. The frameworks will include objective assessment criteria for which sub-services can be procured or developed for the public AI service, including assessments of costs and benefits. A financing scheme will likely be a prerequisite for making this happen.

- The Norwegian Directorate of Health will follow up its recommendation in the report on large language models and will lead the work to develop and establish a common quality framework for testing and evaluation of language models to contribute to safe use of generative AI models in the health and care sector in collaboration with the rest of the health sector. The quality framework should be expanded to include quality assurance of the entire AI service.

- The Norwegian Directorate of Health will follow up its recommendation in the report on large language models, that the health and care sector should collaborate to make more good quality data available for both training (pre-training and post-training), knowledge anchoring (for example RAG), and testing of language models to be used in the health and care sector.

Investigate Fundamental Questions

- The Norwegian Directorate of Health will initiate work to investigate an appropriate organization of national knowledge and information management in healthcare for the AI service, in the short and long term.

- The Norwegian Directorate of Health will initiate work to investigate an appropriate organization of a national AI service that offers targeted health advice or 'healthcare.' The investigation will be seen in connection with the work of the Health Reform Committee, build on previous relevant experiences, and clarify who should have overall responsibility.

- The Norwegian Directorate of Health will initiate work to investigate the need for regulatory changes and what it will mean for responsibility, rights, and obligations to introduce a new type of service that is automated and provides 'targeted health advice.' The investigation will point to appropriate measures to ensure citizens a sound public AI service that responds to health questions.

Overall Plan

Overordnet trinnvis plan for å etablere en offentlig KI-tjeneste som svarer på spørsmål fra innbyggere:

- Assesment of fundemental questions

- Investigate the need for regulatory changes

- Appropriate organization of a national AI service that offers targeted health advice or 'healthcare.'

- Appropriate organization of national knowledge and information management for AI in healthcare

- Establish frameworks

- Make data AI ready

- Establish a quality framework

- Establish frameworks, requirements, and incentives for actors in the ecosystem

- Stepwise implementation of sub-services

- Implement first sub-service

- Implement next sub-service

- Implement next sub-service

- Fundemental activities

- Establish binding collaboration

- Gather experiences nationally and internationally

- Benefits, consequences and financial framework

- Define an AI-service the provides targeted health advise

Les norsk versjon

Offentlig KI-tjeneste for helserelaterte spørsmål

[1] https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10233444/

[2] https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/3112327/id3112327/

[3] Se rundskriv til helsepersonelloven § 3: Lovens formål, virkeområde og definisjoner - Helsedirektoratet og Yter du rådgivning på nett som er helsehjelp?

[4] https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/digitalisering-og-e-helse/kunstig-intelligens/ki-faktaark

[5] https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10233444/

[6] https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/rapporter/report-on-large-language-models-in-norwegian-health-and-care-services-risks-and-adaptations-to-norwegian-conditions

[7] https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240084759

[8] https://www.journalfph.com/index.php/jfph/article/view/6

[9] https://www.jmir.org/2025/1/e66986/PDF

[10] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0736585325000024

[11] https://www.mdpi.com/2076-328X/15/1/88

[12] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1386505625002680

[13] Helsepersonelloven § 3

[14] Rundskriv om helsepersonelloven med kommentarer, Definisjon, Tredje ledd: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/rundskriv/helsepersonelloven-med-kommentarer/lovens-formal-virkeomrade-og-definisjoner#id-3-definisjoner

[15 https://www.regjeringen.no/no/aktuelt/vestre-lanserer-nye-prosjekt-x-piloter/id3115241/

[16] Not published. Rapport fra FHI Helsebiblioteket: En samlet kunnskapsplattform for helsetjenesten, Leveranse på oppdrag i tildelingsbrev: TB2025-10

[17] Not published. Rapport fra NHN: Bruk av KI for å forenkle tilgang til åpen informasjon på Helsenorge og verktøy. Foreløpig status fra NHN sitt oppdrag

[18] https://www.sundhed.dk/borger/patienthaandbogen/

[19] https://ai.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/AIpc2500892

[20] https://datos.live/report/state-of-search-q1-2025/

[21] The risk of hallucinations is high and can be technically reduced through, for example, a RAG architecture that retrieves and displays sources from authoritative databases such as Helsenorge, the Norwegian Electronic Health Library, FHI, SML, and the Felleskatalogen. However, this is not a fully reliable solution.

[22] https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/digitalisering-og-e-helse/kunstig-intelligens/ki-faktaark/ki-begreper-ki-faktaark-1

[23] https://thinkingmachines.ai/blog/defeating-nondeterminism-in-llm-inference/

[24] https://www.stortinget.no/no/Hva-skjer-pa-Stortinget/Nyhetsarkiv/Hva-skjer-nyheter/2024-2025/nordisk-rad-pa-stortinget-kunstig-intelligens-krever-politisk-lederskap/ og https://strategic-technologies.europa.eu/be-inspired/step-stories/openeurollm-european-family-large-language-models_en